Resources

Other Genetics Articles

- Customizing Genetics

- Beat the Heat with Slick Genetics

- The Infiltration of the Dominant Polled Gene is as Easy as 1-2-3

- Breeding for the Future. Are You Using the Right Index?

- Milking Speed Trait Coming August 2025

- Three Tips to Boost Reproductive Performance of Heifers

- Upcoming Genetic Base Change: What to Expect

- Pave the way for a more Profitable Next Generation

- Are you choosing the best index?

- Holstein's Fertility Index Shake Up

- Using HHP$ to Enhance Your Return on Investment

- WWS/Select Sires’ Elite Polled Lineup Leads Industry Ranks

- Genetics In The Drivers Seat

- Genetics Impacting Mastitis

- The Practice of Genetic Culling

- Fertility Matters in HHP$ Index

- Lameness Traits: Underused & Underestimated

- Sustainable Genetic Strategy

- The Genetic Strategy to Improve Sustainability

- Somatic Cell Count Impacts Everything

- Where does selecting to utilize feed fit into your genetic plan?

- Is There Such a Thing as a Grazing Genotype

- Inbreeding vs. Genetic Progress

- Mastitis Resistant Pro

- Recumbency in Holstein Calves

Sire selection is a critical component of herd genetics, as the bulls chosen will influence herd performance for multiple generations. Decisions around which sires to use often attract the most attention because they directly impact production, fertility, health, and longevity traits within the herd. However, while sire selection is critical, it is not the first or in many cases the most foundational step in driving herd improvement.

The WWS ULTIMATE process emphasizes starting with the fundamentals in Steps 1-3: defining herd goals, determining how many dams are needed to create the next generation, and then identifying which females are best suited to create replacements. These steps establish the foundation that allows sire selection to be applied effectively. Without this foundation, focusing solely on individual bulls, even the highest-ranking ones, can limit long-term progress opportunities and reduce the impact of the genetic strategy.

Once the foundation is in place, the focus can shift to customizing genetics. With a clear understanding of the herd’s goals and performance, sire selection can be approached strategically, using tools such as selection indexes and thoughtfully applied cutoffs to achieve balanced progression.

Individual Trait Selection: The Limitations

How many times have you heard something like:

“I need 5 bulls that are over 1250 pounds of milk, positive for DPR, and at least +0.5 on udders.”

While this strategy can screen out sires that have undesirable trait values, it also narrows the usable population to a very small subset. Using the criteria in this example, the full genetic lineup was reduced to only 6 qualifying bulls listed below.

Choosing only from 6 bulls can lead to a few challenges. Any supply issues, price constraints, or close genetic relationship to the herd will further restrict options and flexibility.

While strict trait cutoffs can help screen out sires with clear weaknesses, they may not fully align with the herd’s broader breeding goals. Why were those traits selected for cutoffs? Many herds may emphasize wanting to improve lifetime profitability, yet relying on single-trait thresholds for milk, positive DPR, or udder composite, does not fully capture what drives long-term performance. If lifetime profitability is the goal, then mastitis resistance, SCS, components, fertility, and Productive Life must also be considered. A bull that narrowly misses a milk cutoff may still deliver more overall value through stronger health or fertility traits. Because many economically important traits are genetically correlated or even antagonistic, for example milk yield versus component percentages or fertility, focusing on a single trait can inadvertently exclude bulls that contribute valuable genetics across multiple areas.

The challenge with these cutoffs, is what seems moderate is a lot more aggressive than it appears. For example, a cutoff of +1250 PTAM is actually the 86th percentile of industry bulls for milk. Even a PTAM value of +1000 still places a bull in the 74th percentile for industry bulls. Combining that with additional trait cutoffs, price and supply restrictions, rapidly shrinks the usable sire pool and restricts opportunity in other traits. This creates unintended selection pressure, often in the opposite direction of the herd’s long-term goals.

Use a Selection Index: Your Genetics “TMR”

This is where an index-based approach becomes valuable. A well-designed selection index integrates the economic value of multiple traits (production, health, fertility, and longevity) into a single measure. A selection index can be thought of as a total mixed ration for herd genetics. Just as a TMR combines different feed components to optimize overall cow performance, each bull contributes a combination of traits, including production, fertility, health, and conformation to the herd. A well-designed index balances these traits so that no single characteristic dominates, producing offspring that enhance overall herd performance while maintaining genetic variation. Several industry selection indexes are available, each emphasizing different combinations of traits. Based on the discovery process in Step 1 of the ULTIMATE process, the index that best aligns with the herd’s goals should already be identified.

Let’s assume HHP$ is the index that best aligns with the herd’s goals. The top six bulls for HHP$ are shown below.

All the bulls listed above would have been excluded if selection relied solely on the previous single-trait strict cutoffs. For example, Bull A and Bull E narrowly miss the PTAM cutoff by less than 300 pounds, fall just below or meet the DPR threshold by less than half a point, and are slightly under the UDC cutoff by 0.1 to 0.2. Not only are these bulls just outside the threshold for these traits, both bulls offer considerable advantages in components, productive life, livability, somatic cell score, and mastitis resistance. Excluding bulls like these would sacrifice substantial long-term genetic value for lifetime profitability.

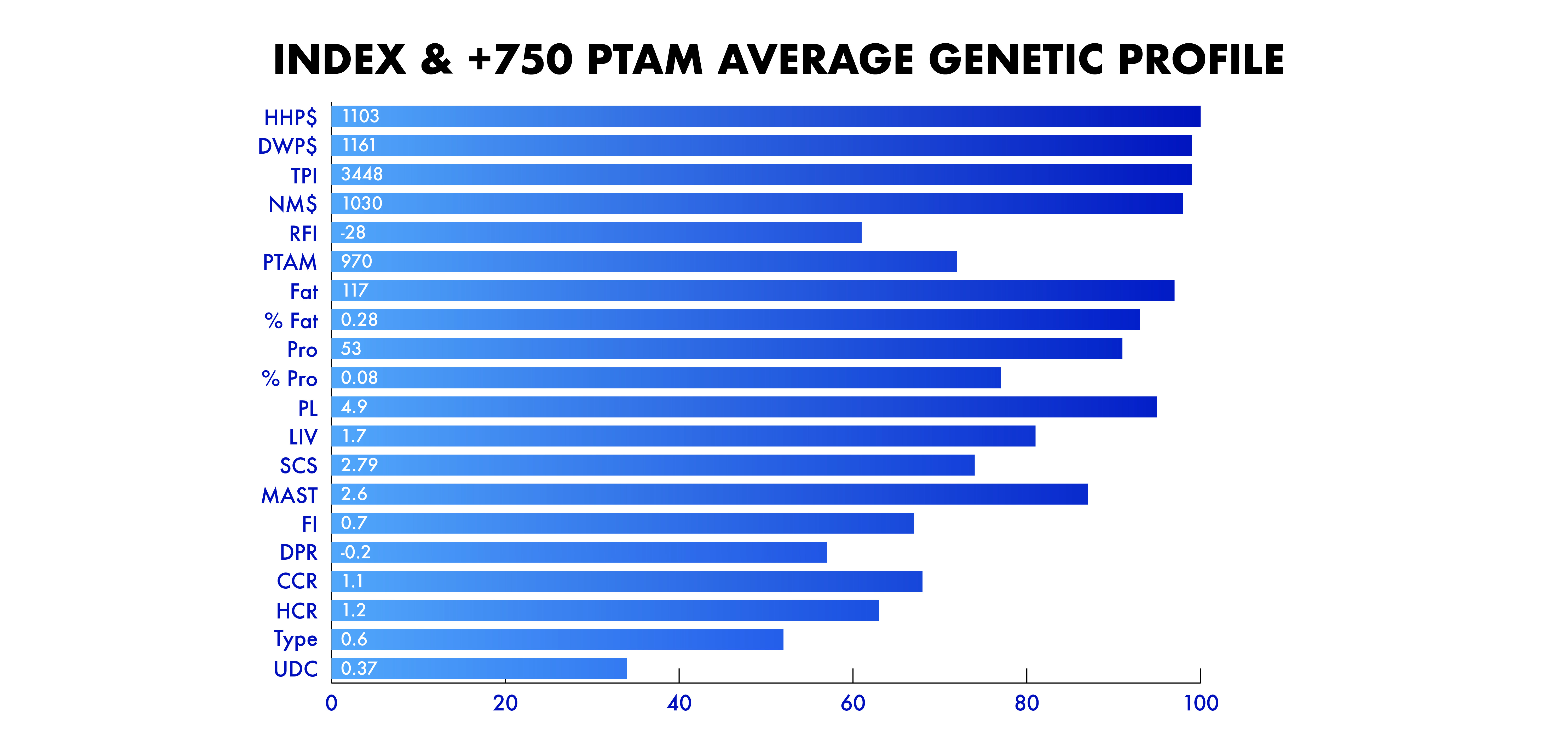

However, genetic progress is not determined by one or two standout bulls alone. Because multiple sires (and females) contribute cumulatively across the herd, it is important to look beyond individual bulls and examine group averages. The genetic profile graphics below present a visual summary of the group’s performance across key traits. Each bar represents the percentile ranking of the group of bulls, benchmarked against NAAB active, foreign, and genomic industry bulls. This comparison not only highlights where the group of bulls excel and where improvement is needed but also provides a clearer perspective on how genetics customized through two selection methods differ across traits.

The cutoff-selected bulls excel in the traits targeted by the thresholds (milk, DPR, PTAT, UDC), as expected. However, the index-selected bulls still perform reasonably in those areas and outperform in components, productive life, SCS, and mastitis resistance, all traits closely tied to health, efficiency, and longevity. While milk averages just under +700, the bulls remain in the top 50 percent of industry bulls for milk, the top 63 percent for DPR, and perform near or above average in other key traits, demonstrating balanced overall merit. Index-first selection ensures that bulls are evaluated based on overall lifetime value, not just isolated traits.

Cutoffs: Helpful, When Used Wisely

Establishing a cutoff is not inherently problematic, as cutoffs can help narrow down a list of bulls. The challenge arises when they are overly strict or stacked together. Applied after sorting by an index, selecting one or two criteria realistically and strategically can be a powerful tool to refine selection without sacrificing diversity or balance.

For example, if the +694 PTAM group average of the index-selected bulls falls below the herd’s preferred average, a PTAM cutoff of +750 can be applied as a starting point. This corresponds to the 41st percentile of industry bulls, maintaining a large, workable population while filtering out the lowest-performing sires. In contrast, a +1250 PTAM cutoff, near the 86th percentile, would eliminate most of the population before other traits are even considered.

The average genetic profile of this refined group is outlined below.

Applying a realistic cutoff in this way increases the group average for milk to around +1000 while maintaining competitive values across other economically important traits. Applying these cutoffs involves a trade-off, as genetic correlations between traits can lead to modest reductions in certain areas, such as udder composite, while improving others.

Conclusion

Using a broader evaluation, such as a selection index, supports balanced long-term genetic improvement by considering multiple traits simultaneously. The index essentially serves as your TMR for genetics, ensuring no single trait dominates. When paired with reasonable cutoffs and a clear herd vision, this approach empowers producers to develop balanced, profitable, and durable cows for generations to come. Customizing genetics is not about chasing the perfect bulls but about building the right replacement population to achieve the herd’s long-term goals.